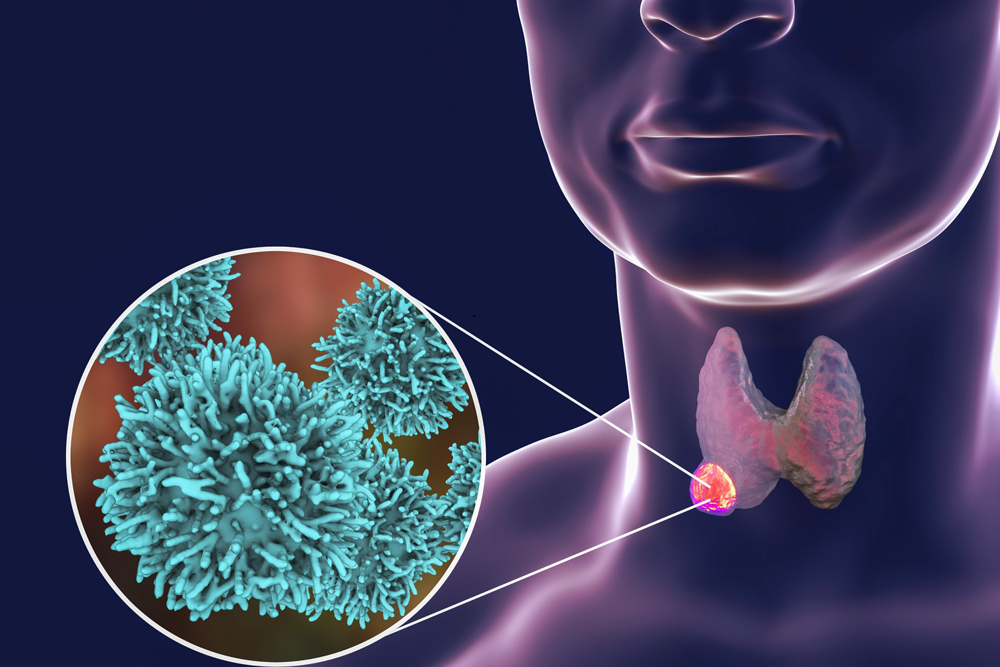

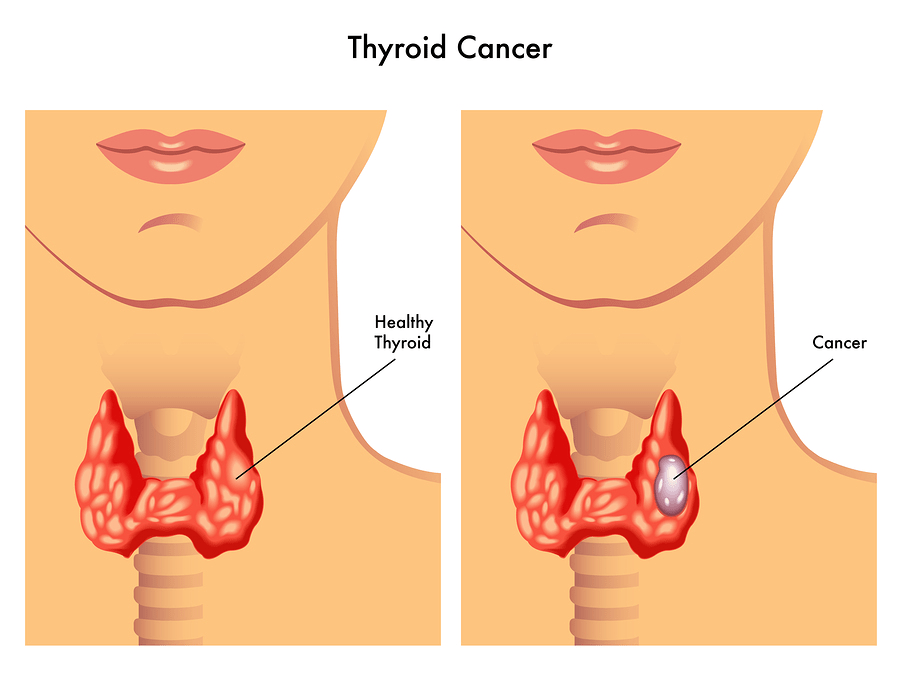

Thyroid cancer can occur in any age group, although it is most common after age 30 and its aggressiveness increases significantly in older patients. The majority of patients present with a nodule on their thyroid which typically does not cause symptoms.